The parkour legend Chris “Blane” Rowat balancing on a rail in London. Summer 2017, a hot day,

“If you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you” – Nietzsche

Humans’ perceptions and instincts are inner signals that can and should be trusted. If you feel you are thirsty, you probably need water. If you feel like something is wrong, it probably is.

Human states have been vastly investigated in the literature. Either in the form of models or scales, they all tried to frame a specific condition considering the individual perceptions produced during the direct stimulation.

These methods of measurement have been implemented in psychology, business, physical activity and so on.

In Powerlifting Mike Tuchscherer proposes a method called Reactive Training System (RTS) which is based upon a rate of perceived exertion (RPE). The RTS puts into a relation the RM percentages for a given lift with the number of repetitions that can be performed with a training weight. Its applications are endless – from autoregulating training based on fatigue to developing a better sensitivity with different loads. (if interest in its limitations click here). Similarly, the classic Borg scale is in an RPE system that is used to measure cardiovascular effort by guessing it subjectively in due course of an activity. It can be used in different forms of testing or as a training tool.

Same Photographer, situation, place, time. See above. However, this time it’s me climbing a rusty tower.

In psychology, different scales have been developed for research and treatment purposes in clinical contexts. Usually, they are validated through extensive testing and a bit more complex than the basic ones seen above.

Just to name two: The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) is used “to assess the severity of symptoms of anxiety” (you could guess right?), and The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) that examines the chronic and the acute state of the art on this topic. Down here you click on the elements I am talking about:

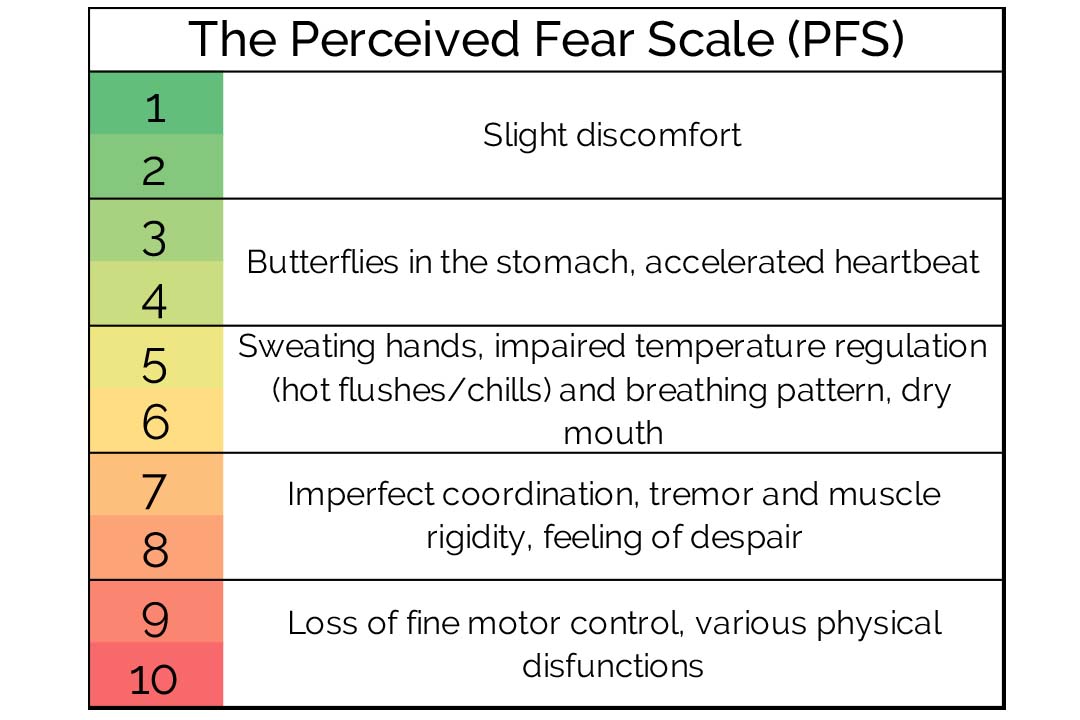

For example, trying to make more quantitative the degree at which an internal emotion is expressed (such as acute fear) can used for exercise selection during practice.

So, check this out:

When setting up a session of familiarization with fear, you should be working between four to eight PFS-RPE. It doesn’t matter what you do as long as you stay true to the scale. Be honest. You might need to regress your sessions a lot or to move them forward according to the stage you are at. Don’t assume you are at a certain stage forever since things change from session to session and we evolve from moment to moment.

Try to assess the current stage you are in a certain condition and move from there.

Gradually progressing into the scale will require a long time, so to make it sustainable – stay in a state you can sustain for a long enough. When training to better handle basophobia (fear of falling) or acrophobia (fear of heights) for example, the time spent at height is everything. You might think you did a great session because the emotions you felt were very intense, but the actual time spent up there might have been too little, therefore the session becomes poor.

The trick to progress in this game is a constant gradual exposure. Start from a manageable drill, work through it, make it harder until even the hardest variation goes from an eight to a three; then start over. On a preparation layer, this is what I call acclimatization to heights.

But, don’t stop here. From time to time retest your skills on a reality base.

This is what makes parkour, climbing, fighting so interesting to my eyes, you can test your level on your skin where the words don’t mean as much as the actual act of doing.

I.e. you can balance on the floor. You can stand at height. Now, be brave, balance at height. There is a lot of learning waiting for you there.

More insights, next week.

Marcello.

Recent Comments